Publish, and be Scammed

Eyes down for the new meaninglessness

“Dear Sir or Madam will you read my book?"

Publication day – when an author’s book finally hits the streets is, for many writers, I suspect and a few I know for certain, less a moment of relief and satisfaction than the latest spin in a cycle of uncertainty so shorn of respite that Dante would have cut it out of The Inferno for fear of dispiriting its scribes. Something less like birth than a round of IVF, a bet on a horse you liked the sound of years ago, but which has yet to run.

Regardless of sales, the writer might once have enjoyed some ceremony, a launch party, something. My last publisher sent me a bottle of wine, I think, though that may have been my agent – anyway, one sent wine, the other flowers. Had something been born or died? They were covering all the bases. By recent standards, from what I hear, even that is decadent – Studio 54 to a texted champagne emoji. But wait, what’s that you’re saying, Flipper?1 A.I generated, print-on-demand pseudo-biographies of authors who are soon to publish? Non-fictional fakes, whose only feasible aim is to mislead what’s left of the book buying public? Let me get into the helicopter…

“It took me years to write, will you take a look?”

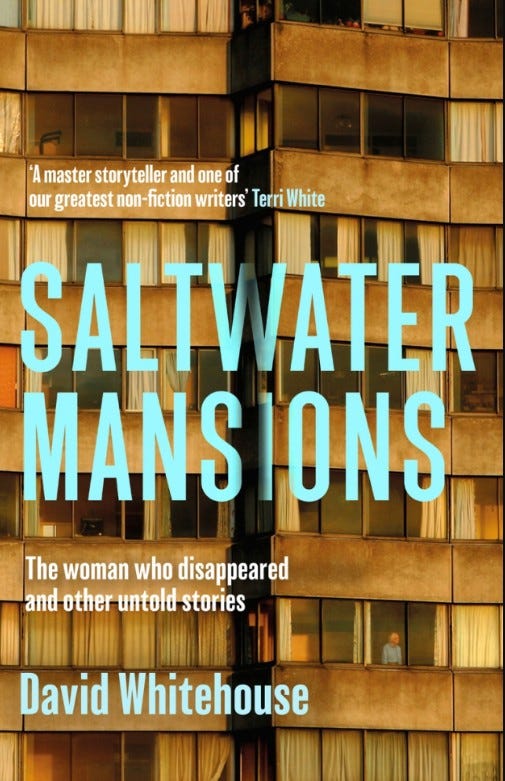

Last week was publication day for my friend and collaborator David Whitehouse’s latest book, Saltwater Mansions, which concerns a disappearance and the things and people he discovered in his attempts to solve it. David’s publisher was good enough to send me a copy and solicit my opinion earlier in the year, to which I responded: “No other writer could go out for a haircut and wind up, years later with a treatise on why we ask, ‘why?’ that reads like a diary, a thriller, a tribute to all the world’s untold stories and the lost art of being unknown,” and I stand by that today. You may learn more, and even buy a copy here: https://www.hachette.co.uk/titles/david-whitehouse-16/saltwater-mansions/9781399621977/

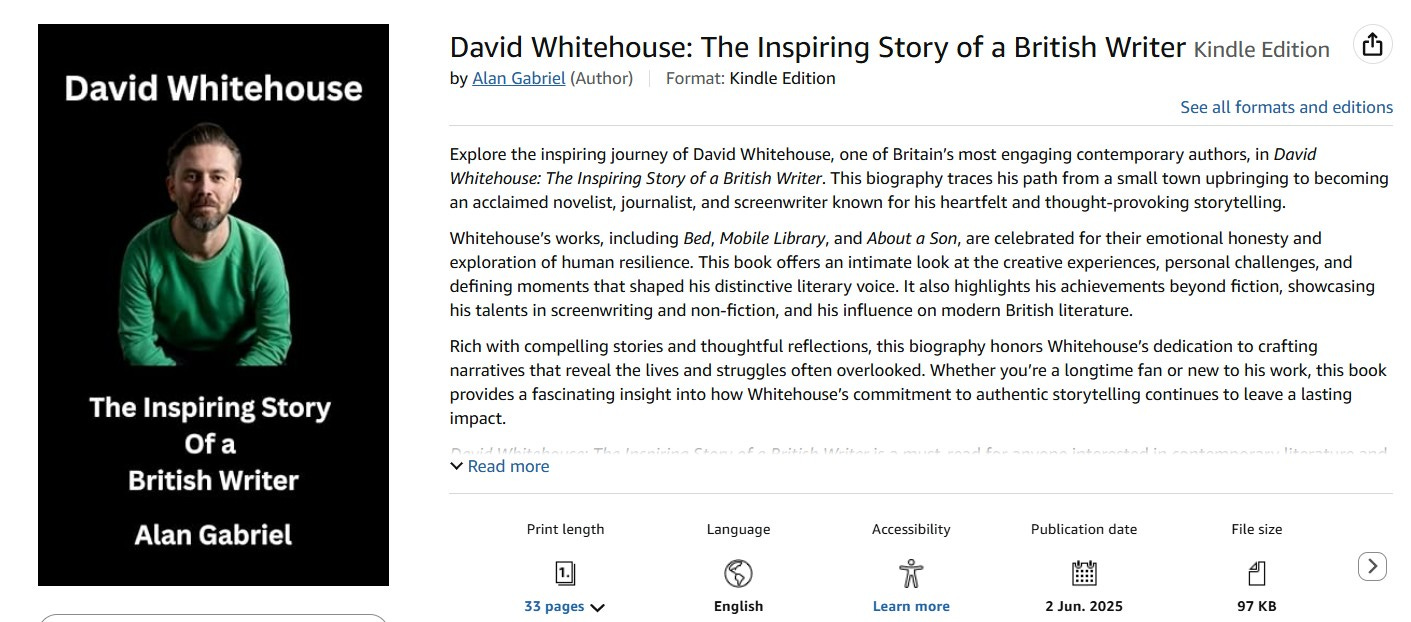

Saltwater Mansions, however, was not the only the only David-based title to drop last week. In the weeks running up to publication he noticed that he had become the subject of a sudden and unauthorized biography.

“It's a thousand pages give or take a few…”

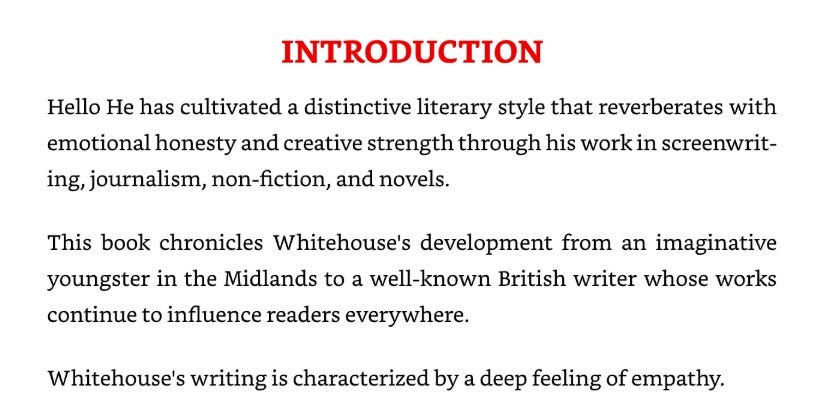

Aware that such things are traditionally the preserve of the far more famous, and that no one had been in touch as yet to speak of this public enquiry into the 40 something years of his life, Dave, asked himself three questions. Who wrote this, why, and what are they saying? The answer to the third question more or less answers the others. Behold, the intro:

“I'll be writing more in a week or two,”

Hello Who writes like that? The answer, almost certainly, is A.I. It goes on, more or less in this vein, for all of 50 pages. Rightly unsatisfied by the online sample, David shelled out for a hardcopy which arrived, still warm from the fundament of the print-on-demand mines, 48 hours later. With his life, at last, in his hands, he reports:

“It gets very repetitive. Like it’s been put through a weird thesaurus of praise until it doesn’t mean anything. It’s insanely boring. And often factually inaccurate. Like I didn’t go to Nottingham university as it claims. And I’ve never talked about some of the stuff it says I have.”

Which is not to say it has no value, I have known David for over 20 years, writing takes up a good part of our discourse, and yet, it was news to me (as well as him) that, “He sees the screen as another blank sheet, one where visuals can have just as much impact as words.” He observes, “the subtle subtleties of human conduct.” And so, with obvious obviousness, it goes on.

“I can make it longer if you like the style,”

The content then is no more than that C-word suggests, content. The motive, naturally, money. “Clever business model really,” says David. “It doesn’t exist until you order it, then just gets printed off by Amazon and posted.”

Alan Gabriel himself? Obscure, at best, even by literary standards. I can’t find any trace of him beyond Amazon, but I’m not much of a digger. David will probably get a book out of trying to find him. “Alan asserts his copyright at the start,” reports David. “He seems to do biographies of writers who have books coming out in the next few weeks. so that people order them by accident, I suppose. And he’s either only just started doing it, or he deletes them from sale after a while.”

Indeed. look upon his works, ye literary, and despair.

Not just the soon to be published, it turns out, but also the published and departed - who happen to be the subject of abiding public interest and a recent documentary.

Here is Edna’s intro:

I’m not sure one ‘does’ anything more socially normative than being born, but what do I know? This is Alan’s domain. I tip my hat in awe, and retreat.

“If you really like it you can have the rights,”

Speaking of retreats I made a futile attempt for a few days to write less, recently, and to think less about writing - which sent me back to the essayist Roland Barthes’, The Writer on Holiday, part of his 1957 collection, Mythologies.

You can, or you could once, spend years in academia exploring what Barthes is on about. I have yet to find the time and so we must accept my layman’s swing at it here. Barthes I think is saying in this essay that the image of a writer on holiday – the kind of thing which was becoming commonplace in the more high minded magazines of his day, is a kind of misdirect. A way in which what he calls society’s “spiritual representatives” are made to look ordinary – but in fact become all the less ordinary having been rendered so. I think he has a point, and if nothing else it tells us something of the status of the writer – and by extension, the written, in 1957. Let’s hear it from the man himself:

this proletarianization of the writer is granted only with parsimony, the more completely to be destroyed afterwards.

He’s saying - I think - that the assertion that writers take holidays like working people is only a way to bring them down to earth briefly before insisting, and perhaps demanding, that they are all the more extraordinary for having done so.

One then realizes, thanks to this kind of boast, that it is quite 'natural' that the writer should write all the time and in all situations. First, this treats literary production as a sort of involuntary secretion, which is taboo, since it escapes human determinations: to speak more decorously, the writer is the prey of an inner god who speaks at all times, without bothering, tyrant that he is, with the holidays of his medium. Writers are on holiday, but their Muse is awake, and gives birth non-stop.

So we are not truly on holiday, just doing holiday type things while not really taking time off at all. A fox, skulking out of the shadows to eat up a kebab, but who will never come out for a pint.

Unlike the other workers, who change their essence, and on the beach are no longer anything but holiday-makers, the writer keeps his writer's nature everywhere. By having holidays, he displays the sign of his being human; but the god remains, one is a writer as Louis XIV was king, even on the commode. Thus the function of the man of letters is to human labour rather as ambrosia is to bread: a miraculous, eternal substance, which condescends to take a social form so that its prestigious difference is better grasped. All this prepares one for the same idea of the writer as a superman, as a kind of intrinsically different being which society puts in the window so as to use to the best advantage the artificial singularity which it has granted him.

Did someone say singularity? Because…

it would obviously lose all interest in a world where the writer's work was so desacralized that it appeared as natural as his vestimentary or gustatory functions.

Clearly, in the age of machine writing, we have arrived at Barthes’ endpoint. The desacralization (the making less sacred) is upon us. Even our clothes (the vestimentary) and digestive (gustatory) systems were more natural than the procedural guesswork of a thousand servers. The writer thus captured is neither on holiday nor sacred, but ever available, all too legible and thus, intrinsically mundane. This won’t be the end of it. The singularity will bring with it similarity. First they came for the biographies, then, one day, by the subtlest of subtleties, everything will be the same.

“And I want to be a paperback writer!”

To recap, and suggest further reading:

The known works of Alan Gabriel.

Precise Instructions… heads into open country for the solstice next weekend, and returns in a fortnight. Try to get by.

‘Flipper’ was a amiable, problem solving dolphin from 60s television, that folks did their level best to understand.

T's friend Alison had a book out last week and was similarly honoured with a biography, this one by Frances Flynn, whose photoshop skills seem second to none. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Alison-Kervin-Biography-Barriers-Journalism-ebook/dp/B0FBKQXN8P/ . I'll be honest, I want one too.

I read somewhere that as more of this stuff appears AI will be scraping more and more unedited AI rubbish and the quality of AI 'literary' output will decline accordingly until it will pretty much implode. It won't stop multinationals from using it to make money but ... AI is brilliant for stuff like spotting cancer cells but for the rest ...? Not so much it seems.