What have sheep ever done for us? Unlike the Romans, there can be little debate about this one. The sheep have given us food, clothing and the resonant metaphor of the shepherd – in return we revile them for their herd instinct, as a means to ridicule our own. This strikes me, like so many of our transactions with the natural world, as something of an unfair exchange.

Sheep have been on my mind this week since I took my seat on a rush hour train opposite someone in this T shirt:

The lower part is obscured in my illicit photograph there – the whole thing reads: “Don’t be a Sheeple – Free Your Mind”. What, I wondered whilst recovering from the cognitive assault of its mangled grammar (although perhaps grammar = conformity in the minds of its target audience), is behind this?

In a city of nine million and a perceived online presence of infinite dimension I am not unsympathetic to the desire to stand out, especially among the young, even in a mass produced T-shirt. The person wearing this was an adult however, one who made a further claim on non-conformity by spending the journey with their eyes closed, as if we, the sheeple, were a poor subject for their incisive gaze. To their credit they were headphone-free, and so not entirely consumed in an act of sensory self-isolation. I respect anyone who can do public transport with their ears open, were mine not preoccupied by tinnitus, I would be noise-cancelling all the way.

Noise-cancelling might be the key to some of this. Festooned for the most part with what even the richest Romans would consider an inconceivable remit of luxury and longevity, we live nevertheless in startled times. As discussed here previously under pressure , even (and perhaps especially) the weakest straw calls out for clutching, and so out of the muddle comes the idea that one must know something special, secret and so on. As such I - the knower - emerge from the flock, become more individual, less drowned. The trade off being that truth is then subordinate to the sense of self-as-believer, the bathwater baby in a demand for identity which precludes a search for meaning. There might be something of this in the current Epstein fever too (some good work by Jules Evans and Sanjiv Bhattacharya on that here and here). But why bring sheep into it?

The sheep - and I have stopped myself from writing ‘humble’ ahead of ‘sheep’, because that seems part of the problem – has suffered a kind of relegation in our minds, and Christianity’s general fall from grace might have something to do with it – but that in itself might have something to do with our growing inability to process metaphor.

Joseph Campbell spoke about this in The Power of Myth:

“The reference of the metaphor in religious traditions is to something transcendent that is not literally any ‘thing’. If you think that the metaphor is itself the reference, it would be like going to a restaurant, asking for the menu, seeing beefsteak written there, and starting to eat the menu.”

We live in the age of the menu eater. Both the fundamentalist and the radical atheist are thus entwined.

For the literalists, the sheep is then part of the problem, proof that a religion which invokes an ovine analogy is implicitly geared up to keep us down. Here’s Christopher Hitchens:

“Shepherds don't look after sheep because they love them - although I do think some shepherds like their sheep too much. They look after their sheep so they can, first, fleece them and second, turn them into meat. That's much more like the priesthood as I know it.”

To be fair to Christopher Hitchens I have always thought his beef (if not his mutton) was with what some of those in religious authority – perhaps even most of those so ordained - do with their power, rather than the spiritual impulse and experience in itself. On that I would not disagree. The point of the sheep/shepherd-as-metaphor, however, “does not point to a deficiency of sheep but to the power, protection, and provision of the shepherd,” says this writer, who also speaks well of sheep’s cognitive prowess in the real world.

The relegation of the sheep then is indivisible from our promotion of ourselves. In our hubristic insistence that we know or are close to knowing all things and that all things can be known - we require a point of negative reference, sheep have become that exemplar. It is not enough that we shrug off the metaphor of the shepherd and go our own way, we have a dig at the flock as we leave. That we need something to look down on while we attempt this ascent should indicate the psychological roots of the action. The quest for knowledge and the fear of being stupid are not quite the same thing – the latter being likely to corrupt what we accept in pursuit of the former. Likewise the fear of disappearing, especially into a crowd, can persuade us into some awful organizations.

Not just outer organizations, but organizations of the mind. I am aware that the rules of Substack have compelled me to designate this as a humorous column, but I have serious concerns here. The age of menu eating, of not just metaphoric failure but a failure to use metaphor in itself and as itself, is a Very Bad Thing. In infancy the ability to symbolize, to make mental representations of things in our world, is a key stage of development. To hold the parent in mind, as a representation which can be relied upon, lessens our dependency on the real and imperfectly available thing. The act of taking out our early frustrations and reparations on a toy is an example of this.

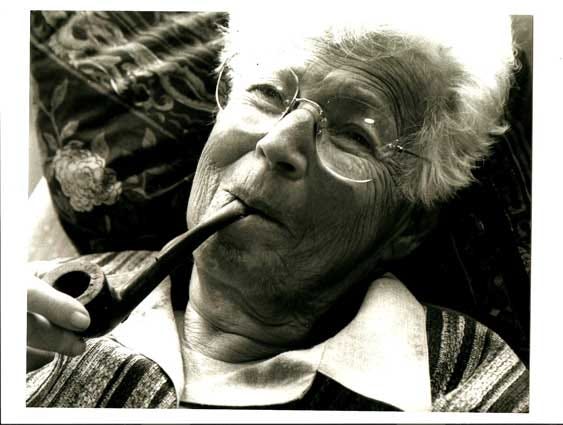

To struggle with symbolization, the inability to form or see the symbol as a representation of the thing (starving because you can’t read the menu or because you have eaten it) are bad psychological news, individually and collectively. Symbol making is the core of creativity, in some ways. Symbolic equation, attacking a chair, for instance, because you think it is your mother (a term coined by Hanna Segal , the pipe-smoking genius of this branch of psychoanalysis) is the psychotic reverse of creative thinking, and indeed of sublimation (taking one impulse and expressing it in another way). Symbolic equation – the fate of our sheep – is on the rise, and this is bad news because in a very real way, civilization IS sublimation.

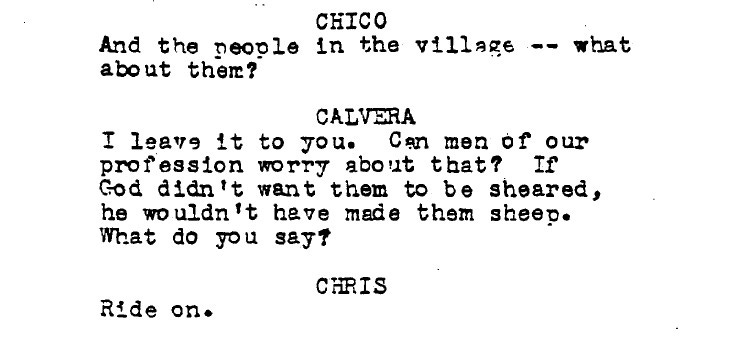

The other twist here is that the sheep as we know and fail to love it, is very much our own rejected creation. The sheep’s ancestor the mouflon https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mouflon is a far feistier, less woolly and compliant creature. We have, in a way, civilized them into something we wanted, whose instincts, honed for our convenience, we now revile. This is quite an act of projection, although it has yielded some wonderful moments in cinema. Exhibit One – The Magnificent Seven:

The fact is, Calvera, God did not make them thus, we did.

Of God and sheep, Exhibit Two – The Great Beauty, here because this scene is scored by John Tavener’s ‘The Lamb,’ and also because whatever Paolo Sorrentino does with the camera when the joggers pass and he follows them into the reveal of the pleasure boat (known in the cinematography trade as a “follow and lead”) yields, along with the music and the narration, something genuinely sublime. And then there’s the dialogue. In case your Italian is rusty, Jep is saying something to the effect of, “It wasn’t enough for me to go to parties, what I wanted was the power to make them fail.”

Passive or not, the sheep we have made are not apolitical. They played a decisive role in the Highland clearances:

“Sheep farming in the Scottish Borders had a long history, but the new sheep carried more meat and wool than the native animals, and needed more grazing land. Mutton and wool were in demand and the Act of Union had opened up new markets in the south. When a flock of ten thousand sheep needed only a grassy landscape to feed it and 16 shepherds to tend it, cottars came to seem an easily removed inconvenience.”

They are also, it is said, taking their toll at the opposite end of the country today: Sheep are destroying precious British habitats – and we taxpayers are footing the bill | Chris Packham | The Guardian

Though not as favoured as the lion and the unicorn the sheep is present in heraldry.

It is harder these days to find those willing to put the sheep front and centre to their work but, not atypically, The KLF were unafraid in this regard.

“you’re dancing all night and then the sun would come up in the morning, and then you’d be surrounded by this English rural countryside … so we wanted something that kind of reflected that, that feeling the day after the rave,”

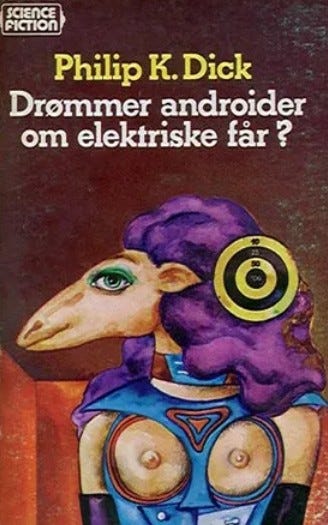

Perhaps in the future, things will be different. In Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream…, Deckard is embarrassed by his electric sheep and craves the status that real animals bring. In a famously prescient work this seems especially salient. One day, all too foreseeable, the sheep we scorn may be a la mode. This is largely absent from modern adaptations of the story, although credit to the Norwegian edition of the book for putting an alluring sheep centre stage - even if the artist might be missing aspects the metaphor in doing so. In an act of restorative justice, this is where sheep ought to be. Perhaps some menus are worth eating after all?

Speaking of the future, Precise Instructions is away for a fortnight now, thank you for your attention and patronage this year. See ewe mid-August.

If you are in need of further reading I commend you to LondonCentric’s piece about fraud and retail in London’s West end:

Shops and the decline of the public realm being a perennial gripe of mine.