"Let Them Eat Pixels."

Kim, Elon and the rest of us.

“Life moves pretty fast,” said Ferris Bueller in 1986, which feels like twenty minutes ago. If anything, Ferris underestimated the issue. Life doesn’t just move fast, it accelerates. Now more than ever, as the premise demands.

Early in December I interviewed Kim Kardashian. At five P.M I cleared my students out of class so that I could speak with a measure of privacy over Zoom. It was dark in London and the call from California and the caller seemed bathed in a kind of unattainable light – a contrast made all the more emphatic by the building’s cleaners attempting to evict me from the classroom while we spoke. Back then I thought they just wanted to go home, today I wonder if they had seen the future.

The days are longer now, but the ebb of seasons is nothing to the news cycle. Los Angeles, where Kim took my call, has seen enough fire and flooding since December to feel like the old testament. America itself slips deeper by the day into a psycho-political contortion which troubles the globe. The idea that I had merely interviewed ‘a famous person’ can no longer encapsulate what happened. Because this is March, the Old Testament has accelerated into the Book of Revelations and if you didn’t hear it coming that’s because the apocalypse is battery powered. Who knew? Well, maybe those cleaners.

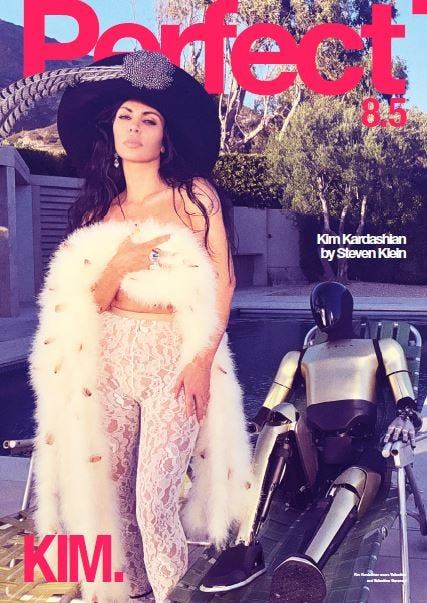

In the four months since the Perfect magazine shoot in November for which I did the interview - all of which comes out this month - being proximal to anything associated with Elon Musk has gone, along with the man himself, from questionable to unconscionable in the eyes of many. Kim - in both the shoot and in the social media realm where she has a degree of supremacy (half a billion followers, give or take) - leant on more than just his vehicle.

Also present that day at Kim’s behest was Optimus – Tesla’s humanoid robot. Optimus is not yet available for sale and so, unlike the Cybertruck, not yet subject to acts of vandalism if left unattended. It will be interesting to see what happens when one of these things can go to the shops for you and pick up your prescription. Robocop may yet require police protection. We are living in a truth stranger than science fiction, what once looked like tomorrow now feels like yesterday.

The pictures ‘dropped’ officially over the last few days and the response has been - predictably - polarising. The interview is not online as yet (I will email a link to subscribers when it is, and update this post accordingly) so I don’t want to share too much of it out of context here. One of the things I love about working for Perfect is that they will run a piece at 3,000 words which is scarcely a thing anymore in the age of short form, silent cars and hasty conclusions. Here is a bit, though:

We are clearly on the cusp of or inside a defining moment about what it means to be human, as well as what the power of those who purvey and profit from our inhuman accessories can or should achieve. So on the one hand we have some striking images of a tech-enabled, female superstar liaising with a masculine android at the edge of a continent. On the other is what this might represent, a symbolic union of spirit and matter, the wedding photos of a transhumanist future, or, if you really want to get excited, the end of the world.

These are merely the more obvious associations, along with the fact that two hugely influential individuals (Kim and Elon) might simply be playing a kind of profitable game – when Kim shares a clip from the day of the shoot, Tesla’s share price surges by 2.1%, financial press speculates that from a trading perspective this offsets a slump caused by the war in Ukraine. Small things have big effects. But before we even arrive at the subject, Kim says, “I think that I am a robot.”

Outside of their political ambivalence - what I like about Steven Klein’s images is their lineage. The woman and (or as) machine is one of the recurring motifs of science fiction.

Forbidden Planet, if I remember rightly, sees Robby the Robot unable to protect his creator, Morbius, because their enemy, “monsters from the id” are the unconscious products of Morbius’ own artificially enhanced intelligence, and Robbie has been programmed not to attack ‘him’ in any form. Robby has been limited according to Isaac Asimov’s (author of ‘I Robot’ illustrated at the top of the page) first law which he laid out in his 1942 story, Runaround: “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.” You don’t need to be much of a historian to guess what Asimov was responding to culturally in 1942. The tragedy (or farce, if we are going to repeat ourselves) is that now as then, this feels like wishful thinking.

The neglect of humanity’s total nature, good and bad, light and shadow, in the pursuit and application of technology is a theme in art long before and throughout science fiction because the unconscious manifests itself through creativity partly as a message to the conscious mind to look out. This is why art made by people is vital, arguably more vital than ever, in an age of imagery and ideas curated and produced by machines. It’s not that the latter are bad per se – but that they contain none of the fruits of human consciousness which is always trying to help itself (i.e. - us) through (and via) crises if we take the time to look and listen to the things we are producing, rather than, like the lady in the poster here, getting carried away by them. To keep the analogy running – it would be like trying to survive by eating pictures of, rather than actual food. Whatever you make of Steven Klein’s pictures, they are ‘real’.

The idea of female beauty ensconced with some inhuman ‘other’ has archetypal roots:

Leda’s swan is not just a swan however, it is Zeus, come to earth in animal guise, because (and Zeus has form here) ‘he’ has become beguiled by what (in a certain analysis) is the beauty of his own creations. The offspring of this is Leda’s daughter, Helen - of Troy and Trojan war fame - and hence we have (I think) another warning from the unconscious about desire and conflict.

As luck would have it, I am part way through a book by the renowned Jungian analyst and author, James Hollis called ‘What Matters Most.’ Hollis is a brilliant thinker IMO who can turn stale concepts fresh with a turn of phrase. One example in the book is his suggestion that God is not a noun but a verb, a process, which is instantly redundant if reduced to or worshipped as a static idea, image, idol or phrase. There is something here which speaks to our primal drive to see something or someone as sacred, or to use another word, iconic.

What Hollis points out wonderfully is that our experience of the sacred or numinous can only ever be represented in kind by a symbol. Symbols, he writes, decay over time into signs, which are taken for the thing in itself but are redundant of real meaning and revered through rites more repetitive than sacred. This is when our idols have not just feet of clay but are false in their entirety. Mythic redundancy. The icon’s decay is the implicit burden of being iconic. We ask too much of ‘things’ because we need more than we can consciously understand. The thing, the image, the person (the parent) which accepts the projection, must face our fury in the end, as must we.

Nothing new under the sun perhaps, except our unprecedented ability to effect and be affected these days. In Rubens’ time or even Leslie Nielson’s there were people who knew very little of each other - in our age of influence, distance is meaningless, discretion is a hinderence, everyone is in on it and I think this might have to change. The Kim piece in Perfect is titled ‘Let Them Eat Pixels’ because the phrase seemed to speak to a situation in which the few beguile the many via a storm of imagery, and that there is a responsibility that comes with that, and a cost. But this is not freak weather coming down from Olympus - this is a storm we summon and crave. If we want to be serious about digital responsibilty we may have to rethink the ease with which and those to whom we lend our gaze. Because these aren’t just clicks anymore, these are acts of faith.

*

In other news this week, if you think Tesla has problems now, wait until alien technology hits the market, or perhaps it’s already here.

Likewise (and also by Jules Evans) if you are weary of Elon, consider turning your attention to the mysterious world of Peter Thiel.

More of me banging on about AI and SCI FI? Be my guest. "A beast that wants discourse" - by Michael Holden

Speaking of guests - fifteen paid subscribers are currently subdising this newsletter - which gets thousands of views. If you would consider rebalancing that economy, consider a paid subscription, even if you cancel it after a single monthly payment and resume free reading thereafter - that’s still a significant and much appreciated help.